Translated from an article in French by Jennifer Champin.

Published by Bateaux.com, one of France’s premier boating publications, on September 24, 2024.

Article ©Bateaux.com. Used by permission. Photo ©QBE

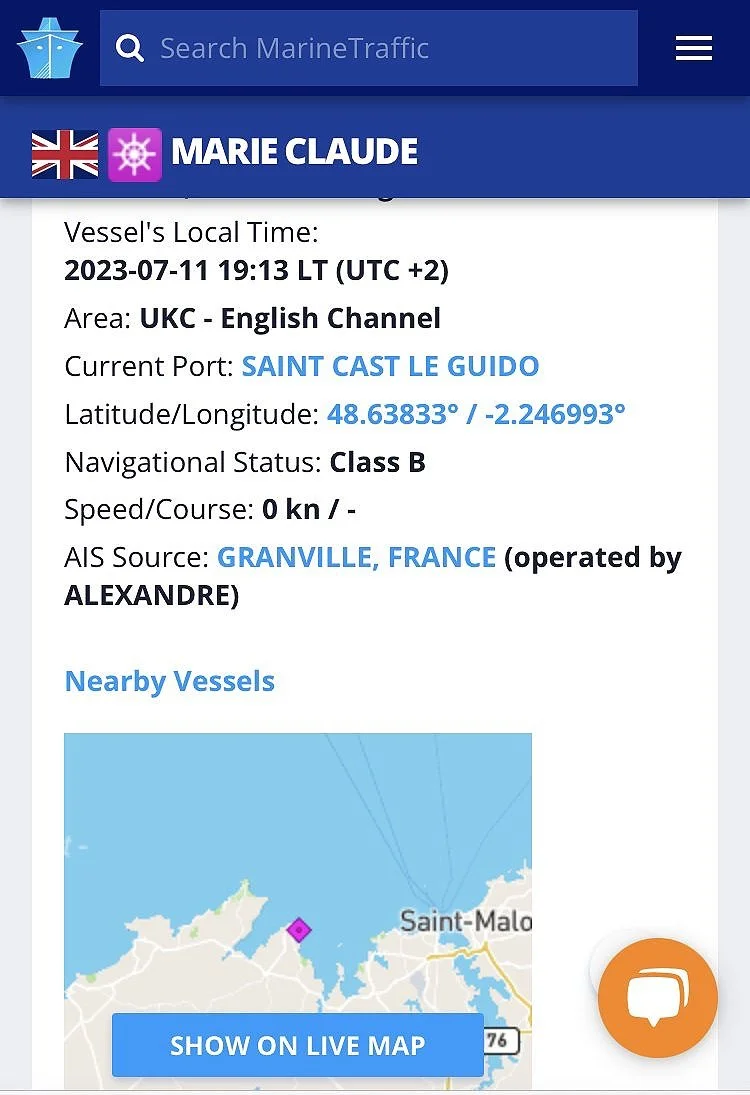

In the world of sailing, some boats are not just vessels for sailing the seas, but powerful tools for learning and personal development. Such is the case of Marie-Claude and Yseult, which have been transformed by Will Sutherland into a veritable floating school for life skills.

Based on his own personal experience, Will has developed a pedagogy of learning by doing that finds its full expression in his QBE Association. Thanks to courses on traditional sailboats, Marie-Claude and Yseult, replicas of the [19th-century] pilot cutter Alouette, he introduces young people to maritime navigation while preparing them for life with transferable life skills. We met him aboard one of them. In the second part of this article, he discusses the essential aspects of his teaching and highlights the challenges of maintaining his cutters.

An action-based method

The pedagogy of Will Sutherland, a native of Scotland, is based on an Anglo-Saxon approach called "learning by doing.” "At sea, mistakes have real consequences. My role is not to tell students everything, but to let them manage, while being present to guarantee their safety and that of the boat," he says. This technique allows young people to confront the realities of life at sea, to master the manoeuvres, but also to develop a strong sense of responsibility. It all starts with simple exercises in port: tying knots, using a cleat, man-overboard drills, etc. Then the boats set out close to the coastline for small exercises; the crews actually have to sail to see how everyone does. Then, when Will feels they're ready, and tells his crew members, "Take me there. Sometimes they don't know where ‘there’ is, but I remind them that all the information is on board. Here, everything is real. If a student makes a mistake, the boat will let them know. It’s the perfect environment for rapid learning."

Will insists on the importance of role-playing: "The students don't understand why I never give a briefing. It makes me laugh. In fact, I prefer the strategy of a debriefing at the end of each outing rather than explaining everything beforehand: ‘Why did you do that?’ ‘What would you do differently next time?’ And after a week, it's amazing to see their progress."

Pilot cutters: robustness in the service of pedagogy

Cutter pilots, historic boats once used to guide larger vessels through dangerous waters, are renowned for their strength and reliability. "They were designed to sail in all conditions, windy or rainy, and to get back into port even in bad weather," says Will. Since 2009, the QBE association has had two of them, Marie-Claude and Yseult, inspired by the plans of Alouette, a pilot cutter constructed in France in 1891 by François Lemarchand.

Will’s sailboats, built in Falmouth in Cornwall, are real learning platforms for the immersion courses offered by QBE. "The pilot cutters are stable and above all very safe, which allows you to concentrate on the technique without constantly worrying about speed. Rigging adjustments on these boats can add 1.5 knots of speed. Still, if they [the sails] are set incorrectly, everything works fine, it's just not optimal," says Will.

On board pilot cutters, every manoeuvre matters and every miscue can have immediate consequences. "Old-fashioned sailing requires constant attention. You have to know your rigging, know how to read the sea, and anticipate each change in the wind," insists Will before continuing: Nevertheless, young people learn to be self-sufficient very quickly, because they are immediately confronted with the demands of the sea." For the participants, daily life on board always requires discipline. They are responsible for everything: the helm, the sails, the meals... There is no leeway for passivity.

Thanks to the support of the association's skippers, the young crew members learn to manoeuvre the traditional boats with their complex gaff rigging. It is a technical challenge, but also an undeniable return to the roots of sailing for the founder of QBE: "This total immersion in the management of a cutter forges characters and instils fundamental values of rigor, initiative, and solidarity.

The Challenges of Maintaining Old Gaff-Rig Boats

Boat maintenance quickly became an unavoidable priority. "Taking the boats out of the water every year to check the hull and change out certain parts of the rigging is essential to guarantee their safety and longevity," says Will. Each season begins with lots of meticulous work: application of antifouling, checking of thru-hull fittings, etc. Older boats like ours require constant attention to ensure their performance and safety at sea.

In the 1960s, the transition from wooden hulls to plastic and fiberglass ones marked a new era for “classic” boat construction. Nevertheless, despite taking advantage of innovations in hull fabrication, the rest of our boats’ structure remained wooden. "The builder started with small 16-foot boats, then 22-foot boats, and finally 28-foot boats that sold well," Will says. A certain Mr. Dupré, a French architect, ordered a 28-foot racing model, equipped with a flush deck, an enlarged mast and a longer bowsprit. This boat, designed to carry a lot of sail, has distinguished itself in regattas, particularly at the annual events at Falmouth. After several victories, Dupré asked the builder to make him a larger ship to accommodate his entire family. The plans for Allouette were chosen because it sailed for 40 years, beginning in 1891, "which was exceptional for the time, given that most boats were expected to last only 20 to 25 years," says Will.

Boat maintenance quickly became an unavoidable priority. "Taking the boats out of the water every year to check the hull and change out certain parts of the rigging is essential to guarantee their safety and longevity," says Will. Each season begins with lots of meticulous work: application of antifouling, checking of thru-hull fittings, etc. Older boats like ours require constant attention to ensure their performance and safety at sea.

In the 1960s, the transition from wooden hulls to plastic and fiberglass ones marked a new era for “classic” boat construction. Nevertheless, despite taking advantage of innovations in hull fabrication, the rest of our boats’ structure remained wooden. "The builder started with small 16ft boats, then 22ft boats, and finally 28ft boats that sold well," Will says. A certain Mr. Dupré, a French architect, ordered a 28ft racing model, equipped with a flush deck, an enlarged mast and a longer bowsprit. This boat, designed to carry a lot of sail, distinguished itself in regattas, particularly at the annual events at Falmouth. After several victories, Dupré asked the builder to make him a 46ft cutter to accommodate his entire family. The plans for Allouette were chosen because it sailed for 40 years, beginning in 1891, "which was exceptional for the time, given that most boats were expected to last only 20 to 25 years," says Will.

This model, named Marie-Claude, attracted the attention of an English banker who built a replica named Yseult in 2000. The builder had started work on another, even larger, boat when his untimely passing at the age of 55 brought the project to a halt.

"After his death, the yard was sold, and all the molds of the boats were lost or destroyed. For me, these boats are unique, almost impossible to reproduce. Today, building such ships would cost a million—or even 1.5 million—euros, a colossal investment," says Will, proud of these 46ft (14m] boats he acquired in 2009.